More than a subject of experimentation, the architecture of water is a culture that pushes boundaries, a utopian dream, a new way of living in the world. As increasing population growth and the impacts of climate change give us a glimpse of the positive and negative impacts of water, cities are examining the potential of their waterside spaces. A complex, stimulating vision that generates solutions.

THE DIALOGUE BETWEEN ARCHITECTURE AND WATER

Modern urbanism expresses this need to protect our coastal spaces and celebrate nature. The resulting harmony demonstrates the evolution of our collective consciousness and our respect for the coastline.

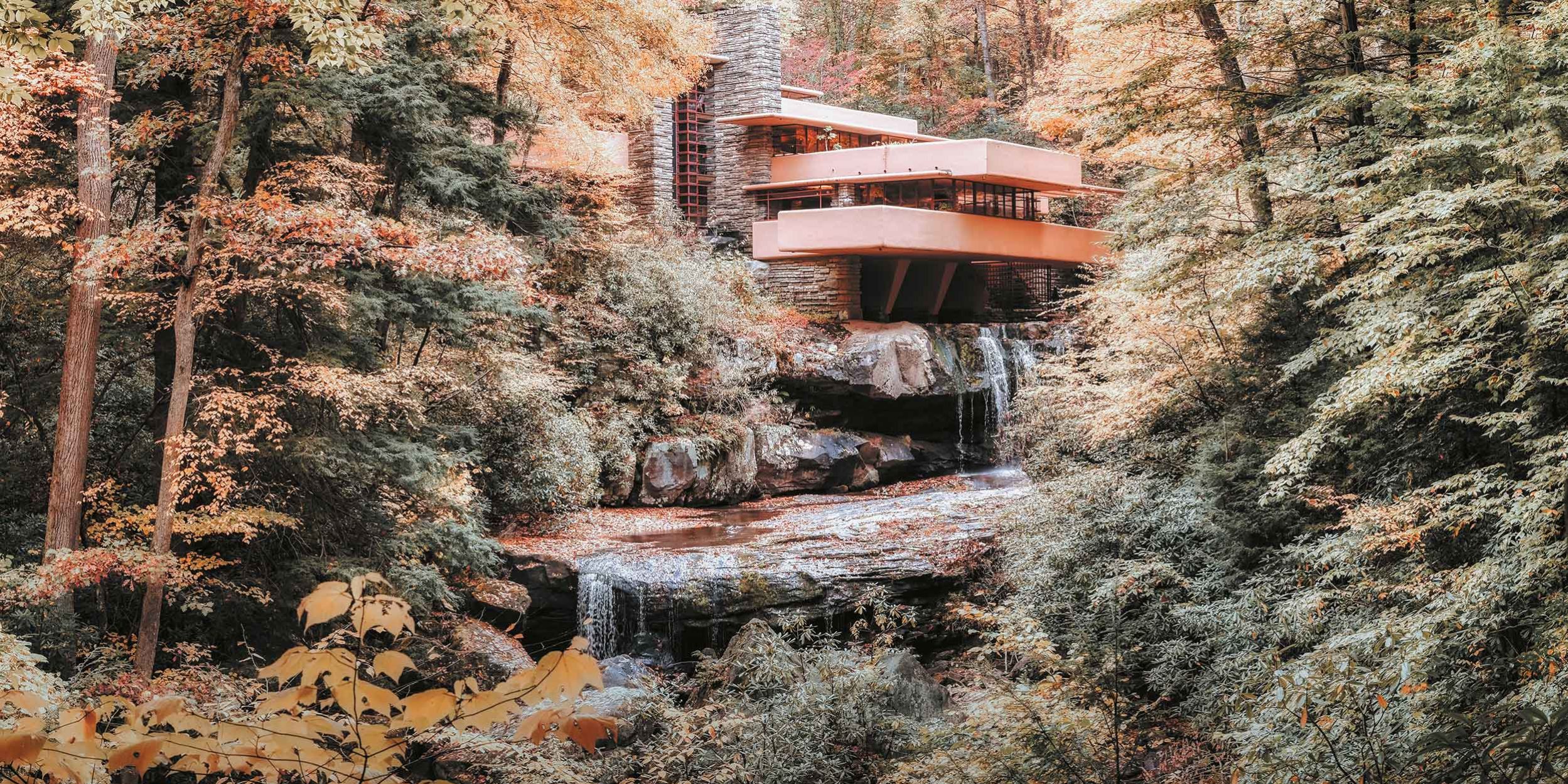

Construction is solid matter, while water is liquid. The balance between the two can be a source of challenges. To allow for a dialogue between water and architecture, the presence of the water must be strengthened rather than eliminated. The structures that emerge from this dialogue create an admirable link between the water and the land, humans and their canvas. This trend is part of a desire to celebrate and support the environment instead of dominating it.

Fallingwater, from architect Frank Lloyd Wright, which seeks to reinforce the waterfall rather than repress it, is an excellent example.

WATER AND DESIGN

Water shapes design, and its impact isn’t limited to residential designs.

Den Blå Planet, the Blue Planet aquarium located on the waterfront in Copenhagen, Denmark, is inspired by the whirlpools of the sea and schools of fish. Its rounded architecture reproduces the organic movement of water, promoting intuitive navigation of the site. Resembling a whirlpool, the access area immerses visitors in a world of its own marked by a naval atmosphere.

In northern China, the Harbin Opera House, designed by the Chinese firm MAD Architects, unveils a harmoniously open architecture on the outside, unfolding in the heart of the wetlands around the Songhua River. Like a landscape, this architectural masterpiece features flowing lines that seem to have been created by the wind and water.

Lanjarón, a city in the south of Spain known for its spas, has seen its former slaughterhouse turn into a water museum. A project from architect Juan Domingo Santos that highlights the industrial architecture of the age while opening the doors to a new story: that of water. Along the Lanjarón River, a contemplative space takes shape where the omnipresence of water on the ground is dominated by plays of light and shadow. Historical and modern styles live together in harmony, while the emergence of contrasts in the choice of materials creates echoes and reflections, transforming the pavilion into a space that awakens the senses.

WATER AS A HABITAT

With the growing global population and rising sea levels, architects are looking for ideas to build the world of tomorrow: vertical constructions, constructions on water, and —surprisingly— underwater constructions. This aquatic architectural deployment is a necessary answer to modern problems, to the greatest delight of water lovers.

For several years, Dutch architects have been studying the creation of structures that are in harmony with the coasts and the sea. At the Port of Rotterdam, a float-ing pavilion initiated by DeltaSync and built by Dura Vermeer is a first step toward floating urbanization. For the moment, the pilot project serves as an event and artistic space, but in the long term, the contractors aim to develop a whole community of floating homes.

In Amsterdam, the IJburg district is built entirely on water using artificial islands, but some of the houses simply float on water. Indeed, to mitigate the sudden rise in water levels and prevent floods, floating homes have been built, making it possible to adjust to the movement of the waves and the impacts of the elements naturally.

“When Water Meets Architecture,” an exhibit at the Loire Marine Museum, answers the question of how to adapt architecture to the fluctuating presence of water—a global issue for several years now. Inspiring and contemplative, water can also become complicated and formidable in the event of a natural disaster. The exhibit highlights alternative solutions, presenting achieved or invented projects that incorporate water in different ways: floating or underwater architecture, inhabited bridges, lakeside communities, etc. As a new territory to be developed, water becomes a fully fledged architectural element. It gives rise to a form of architecture with the flowing, moving lines present in marine, river, and lake environments.

In the imagination of tomorrow, cities are also invited to go underwater. The visionary architect Vincent Callebaut presents Lilypad, an amphibious, self-sufficient city.

Incorporating a large underwater reservoir, the project is imagined to be developed both above and below water. Designed to be placed in the middle of the sea, Lilypad adopts the curves of a giant Amazonian water lily—a floating platform that harmonizes with the movements of the water. Housing, business, and leisure spaces would take their place around the central lagoon, which would collect filtered rainwater. Studied at the United Nations and the European Parliament, Lilypad is a project that is both visionary and utopian.

For nearly a decade, schools have also appeared on the water. The floating schools from Nigerian architect Kunlé Adeyemi, recognized for the Makoko Floating School in Lagos, Nigeria, evoke this need to transform the way areas around water are urbanized by creating a sustainable, eco-friendly, alternative construction system for the large populations of coastal regions. The Makoko Floating School adopted an innovative approach to meet the social and physical needs of the community by considering the impact of climate change and the rapid urbanization of the African continent. The Makoko system is a modular, floating, and durable prefabricated wood structure that can quickly and manually be assembled and disassembled on the water. Although the pilot project collapsed in 2016, it has been successfully deployed in five countries on three continents, and the reconstruction of an improved version has been promised in the coming years.

CELEBRATING WATER

Fountain House is a creation of the German collective Raumlaborberlin in collaboration with the Goethe-Institut Montréal and the Quartier des Spectacles. Presented in 2014 on Esplanade Clark, the project overturned the notion of water as a public good taken for granted, emphasizing free access to it. In the heart of Fountain House, a thin waterfall pours through the roof. Collected in a small basin and redistributed into the air in the form of a refreshing cloud, water was rethought and reinterpreted as a fundamental element of life. Facilitating communal living and participant interaction, Fountain House became a place of celebration and sharing.

SOURCES

-

Bader, Markus. « Fountain House ». Raumlaborberlin, 2014

-

Gimbal, Julie. « L’eau, source d’architecture. Partie 1 ». Lumières de la ville, 10 janvier 2017

-

K-Hoh, Sipane. « Quand l’eau devient source d’inspiration ». Détails d’Architecture, 17 juillet 2014

-

Maneval, Virginie. « Sphère 2010 Dura Vermeer — Pays-Bas, Rotterdam ». Bubble Mania, 28 novembre 2017

-

Morain, Odile. « Et si la ville de demain se faisait sur l’eau. ». France Info Culture, 5 mai 2015

-

Musée de la marine de Loire. « Quand l’eau rencontre l’architecture ». Châteauneuf-sur-Loire, France, 16 mai au 21 septembre 2015

-

NLÉ. « Makoko Floating System ». NLÉ Works, 2011

-

R, Hasina. « Lilypad de Vincent Callebaut, une ville amphibie pour les migrants climatiques ». Batimat, 14 novembre 2018

-

Rik, Neven. « Les avantages incontestables de construire sur l’eau ». Architectura.be, 11 août 2015

-

Urban Hub. « Eau et design fusionnent pour une nouvelle architecture sur les fronts de mer urbains ». Urban Hub, Des villes façonnées par l’homme, 4 octobre 2018