A few years ago, I knew someone who was being pushed out of his home by all the things he owned, as if chased off by the stifling abundance and compact disorder that covered every surface of his apartment.

It was an ordinary mess, made up of a thousand little decisions constantly postponed and fueled by a thousand little fears. The remains of a changing life in a paralyzing heap, here on the table, there on the floor.

I remember the clothes strewn on the floor, the jumble of papers and little pieces of trash on the kitchen table. The fridge filled with Mason jars that threatened to toss their lids like Frisbees across the kitchen under the effect of fermentation ignored for too long. I see him again, standing in the middle of the crowded room, holding in his hands the souvenirs of a trip he hadn’t taken, brought back by an ex who had left him three years earlier. He stood there, motionless, surrounded by the remains of his past projects: a dead kombucha starter at the bottom of a jar and broken musical instruments.

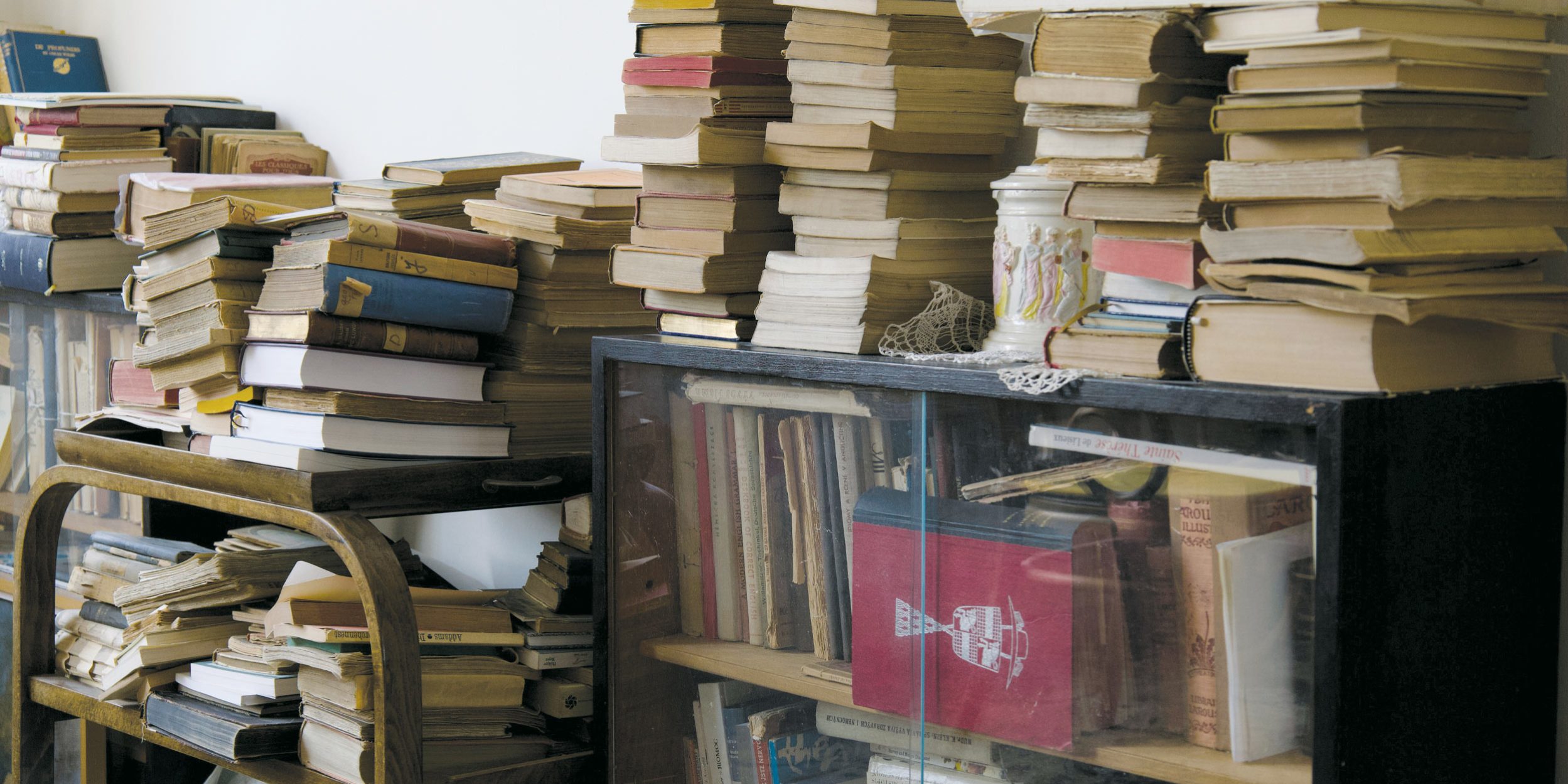

I remember books, everywhere. Pressed against each other on a long shelf above the sofa, there were books that had influenced him and nourished his love of literature, as well as philosophy books that he kept, as he told me, to seem intelligent. There were books he had started but never finished, which imposed themselves on him with insistence like so many crushing tasks on an old to-do list. Finally, hidden in a corner of the office, there were university textbooks to which he seemed to have entrusted a part of himself—the prospect of another life, placed for two decades on the back burner of possibilities.

“Abundance no longer opened up possibilities; on the contrary, it crushed them.”

When I met him, the chaotic abundance of the apartment took up all the space. The heavy accumulation of books had taken away his desire to lie down on the couch with a novel. The clutter on the counters no longer allowed him to undertake the cooking projects that seemed to bring him so much satisfaction. And the surfaces on which he could have set up his computer to work and create now displayed a multi-layered disorder hostile to concentration.

Over time, the excess—steeped in fatigue and fueled a little more each day by discouragement—became increasingly dense, increasingly complex to tackle, increasingly confronting. He had gotten into the habit of eating all his meals at a restaurant. He no longer dared to invite anyone to his house. However, he knew that when he opened the door to his home in the evening, he would be greeted by despondency and anxiety at what had become obvious: all the things he had held onto until now, all the things he thought defined him and allowed him to lead a rich, full life—these things were now suffocating him. Abundance no longer opened up possibilities; on the contrary, it crushed them.

This guy was the friend of a friend, and one day, he wrote to me asking me to help him “organize his life.” Helping people declutter is what I’ve chosen to do. It’s a job I love, because it gives me energy and allows me to be in the heart of the action, but above all, because it places me on the exhilarating threshold of new beginnings.

On the morning of our first day of decluttering together, we were sitting outside on the steps of the duplex where he lived. He looked both overwhelmed and annoyed, but I think he was a little afraid, too. To help him pull himself together, I remember telling him to act as if nothing inside the apartment belonged to him anymore. As if he were free to leave it all behind, if he wanted to. The image took effect: he deflated as if an enormous pressure had just left him. It was as if he could see himself on the other side of this exercise, in a world where he didn’t feel guilty or responsible for a bogged-down apartment. So, he plucked up his courage, and we headed inside.

Over the weeks that followed, we tackled the excess room by room. We sorted through camping gear, collected important papers, and made piles of books to give away or return to their owners. We threw out almost everything in the fridge and managed to get the kombucha starter out of its jar. We donated musical instruments and clothing, dragged furniture out to the sidewalk, and identified tasks to be completed in order to keep moving forward.

Each day, he faced a flurry of decisions and went through all sorts of little periods of mourning, but in the same breath, he defined a new version of himself, clearer and more honest. He raised his head and regained his power. Each day, he felt a little lighter, prouder, and more confident of the work he had started on his knees and finished standing, galvanized by this transformation and his ability to transform himself again.

Several years later, I sometimes cross paths with him in my neighbourhood. He often tells me how liberating the decluttering we did together was. That it allowed him to build a positive self-image and see himself in a future that really suited him. And hearing that is nourishing for me. It’s what drives me to seek out my place on the threshold of new beginnings, on that bright tipping point toward greater freedom.